The Density of Unexpected Encounters

1. 11. 2022 / Derek Sayer

(This picture comes from Derek Sayer's upcoming book Postcards from Absurdist...

23. 9. 2022 / Marci Shore

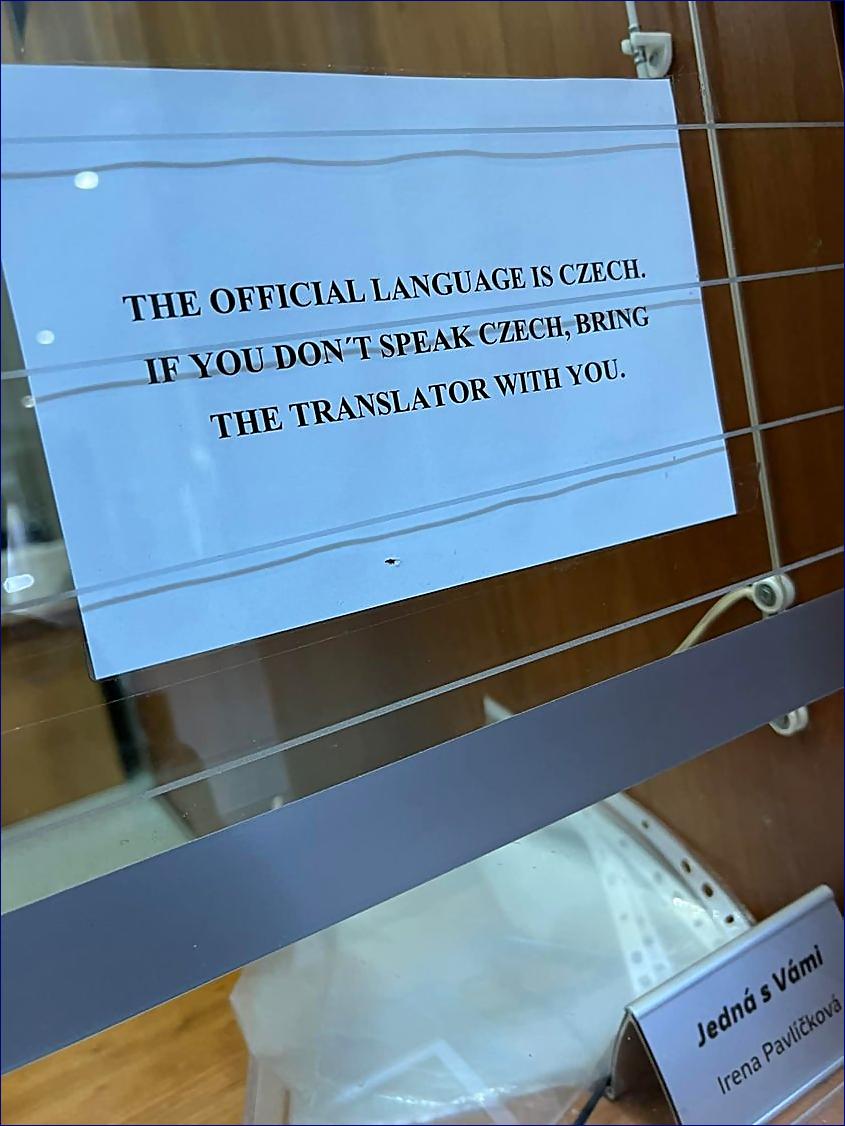

Photo: From a Czech government office.

* * *

In May 2021, Jill Massino and I organized a roundtable at the annual congress of the Association for the Study of Nationalities in New York. It was entitled The Benefits and Burdens of the “Invisible Suitcase”: Writing Contemporary History as an Outsider.

Some of the greatest historians of the contemporary period are “outsiders” to their country of study, for instance Robert Paxton and Christopher Browning in the case of France and Germany during the Second World War. Outsider perspectives enhance, complement, and complicate existing narratives, and, as such, help to produce a more nuanced and complex portrait of the past. Yet our collective experience is that Western historians of communism in Central Europe struggle to establish their legitimacy among societies that remain attached to an ethnonationalist definition of identity. Also, many people believe that only contemporary witnesses are entitled to speak about contemporary history. This roundtable offered the cumulated experience of four scholars: Marci Shore, Jill Massino, Jan Čulík, and Muriel Blaive. We reflected on the way in which our status has affected our research, our writing, and our reception. As a result, our roundtable also offered insight into the societies we are studying and into the stakes involved in the production of history.

Britské listy has kindly offered us to publish our texts, as well as a few others on the part of colleagues who attended the panel and participated in a very lively discussion. Here is the first one from Marci Shore (Yale University).

Muriel Blaive

Ostranenie, or the Epistemological Advantages—and Disadvantages—of Marginality

Marci Shore

One evening in early spring of 2000 I gave my first public lecture presenting my dissertation research. The topic was a circle of avant-garde Polish poets born around the turn of the century who, each in their different ways, found their way to communism in the 1920s. The setting was a literary museum in Warsaw in whose archives I had been working for months. The language was Polish. I spoke for some fifty minutes, and then the moderator invited the audience to ask questions. A middle-aged woman stood up.

“You,” she said to me, “are a young person from another continent. You are in no position to understand Poland.

I had no idea how to respond. After all, the woman had not addressed the content of what I had said; she had addressed my right to speak. And if I had no right to speak, what was I doing there? In any case, it was too late: I had already given the lecture.

Mercifully, a journalist in the audience, a Polish woman my own age, stood up on my behalf. To this day I feel terribly grateful to her; she spared me having to respond myself, and I knew neither what I wanted to say, nor what I should say—moreover, I feared the older woman had a point: what right did I have to be there? I had not lived and suffered under communism as those in my audience had. I spoke Polish like an American graduate student. Moreover, what can we ever understand about the experiences of others?

Remembering that evening today, twenty-two years later, I do not feel indignant. If I do, though, feel somewhat less insecure now, it is not because I believe that I have come to understand Polish history as Poles understand it, but rather because I feel more confident now of the value of different points of entry. Some things I will never grasp with the intuition of insiders; other things I will see more clearly. Each subject position carries its own epistemological advantages and disadvantages. The idea that there is a given perspective—be it from the inside or from the outside—that yields absolute truth is an epistemological fantasy.

To use an analogy from Husserl’s phenomenology: there is no position from which it is possible to see all sides of the cube in a single gaze.

***

In his essay “The Non-Jewish Jew,” Isaac Deutscher—the Galician Talmudist prodigy-turned-Polish-communist-turned-Trotskyite-in-British exile—told a story of a Jewish tradition of breaking with Jewish tradition. The moral of this story was the epistemological advantage of marginality. Crossing borders, hovering on peripheries, allows one to relativize one’s own experience, beliefs, and culture. Liminality, in Deutscher’s telling, becomes a privileged position from which to disentangle the particular from the universal.

It is difficult, for instance, for those who are monolingual to understand grammar as such. Only a comparative perspective allows for some metaunderstanding. Monolingualism, common among Americans, is more than a linguistic deficit; it is also an intellectual handicap: an inability to grasp not only how language can structure thoughts, but also how life in a different language can be equally real. When my son was five years old, his two young kindergarten teachers took into the class, in the middle of the year, a five-year-old boy who had just arrived as a refugee from Homs, a city utterly leveled by bombing during the Syrian civil war, whose photos eerily resembled the photos of Warsaw in 1945. Neither the boy nor his parents spoke any English. My son (who is bilingual in English and German and has some understanding of Polish) did not speak any Arabic; he could not understand his new classmate’s language any better than the other children. Yet what I found gratifying was that my son understood conceptually what it meant that this boy spoke a different language. My son knew what it was like to code-switch. He knew what it felt like to be in a place where he spoke the language. And he knew what it felt like to be in a place where he did not speak the language. And he knew what it felt like to be in a place where he understood some, but not all of what people said, because it was a language he was familiar with, but did not speak well. He knew that not speaking English did not mean that the boy from Syria was stupid; and he knew it was frustrating and sometimes maddening and very frightening not to understand.

Relativism and empathy are not the only epistemological advantages of marginality. There is also what the Russian Formalist Viktor Shklovsky called ostranenie, estrangement or defamiliarization. For Shklovsky the purpose of poetic language was to make the familiar strange, to shake us out of our habituation, to jolt us into not merely recognizing (uznanie), but truly seeing (videnie) the world around us. The language of poetry, Shklovsky explained, was and should be laborious and impeding, disorienting. And just this sense of disorientation, of the world made strange, could cast a light on what was otherwise muted by shadows.

For Shklovsky habituation caused us to sleepwalk through life. It condemned us to automatism, and deprived us of our own experience. This habituation—it seems to me—is not unrelated to our remarkable human ability to normalize the abnormal. It is arguably the coping mechanism that allows people to survive wars and other catastrophe. Yet it has its dark sides. Americans are often unaware, for instance, of the extent of our habituation to the omnipresence of guns, to shootings, to violence—until we are confronted with the shock of a foreigner.

The tendency for repetition to dull vivid seeing into the more impoverished recognizing can help us make sense of many anecdotal examples. For instance, the classic account of early American democracy was written by a French visitor to America. Or the Polish film director Agnieszka Holland was the first person to tell me—and hundreds of others in Vienna’s Burgtheater in late spring of 2016—that Donald Trump would win the American presidential elections. Or, when in 2014 the Kremlin instigated a grotesque war in the Donbas, the American-trained Japanese historian Hiroaki Kuromiya became a celebrity among Ukrainian students. Kuromiya, a professor of Soviet history, is the author of Freedom and Terror in the Donbas: A Ukrainian-Russian Borderland, 1870s-1990s. A decade and a half after its publication, this became the book that young intellectuals from the Donbas turned to in trying to understand their own home, their own history, their own situation

One further example, which I realize is utterly outside my expertise but begs to be mentioned: perhaps it was not a coincidence that it was a neuropathologist from Nigeria, Bennet Ifeakandu Omalu—for whom American football was alien—who made the breakthrough discovery of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy in football players.

I know nothing about neuropathology (and nearly nothing about American football, for that matter), but I nonetheless felt a certain connection to Omalu’s story. There is a lack of inhibition that comes from not having internalized the taboos of others. When, several years after I gave that first public lecture in Warsaw, my book about the avant-garde poets appeared in Polish translation, I found myself answering question upon question put to me by Polish journalists. Among the repeated tropes that struck me was one that went like this: “Where did you find the courage to write about Wanda Wasilewska?” (Wanda Wasilewska was a Polish socialist-turned-Soviet communist writer and activist whose name has long been anathema in postwar Poland; she is seen, with some justification, as having personally delivered her country to Stalin.) To me the very question revealed a misunderstanding. Writing the book demanded an enormous amount of work: I did research in some seventeen different archives in five different countries. I would like to believe that writing the book involved a little bit of talent as well. But not courage, not as such. I had not grown up with Wanda Wasilewska’s name surrounded by horror. I had not grown up with Wanda Wasilewska’s name at all. For me there was no taboo to overcome. There was no fear—not because I am braver than Polish historians, but because I had no a priori affective relationship to this historical character.

I thought of this again in the years following the Ukrainian revolution. In 2014 and 2015, as I was working on a book about the Maidan, I listened to Vladimir Putin on film clips, in speeches and interviews. I had no illusions about him; it was not pleasant to listen to his lies, but I could nonetheless listen and take notes, notice phrases and allusions that stood out, think about how I would illuminate their implications in what I would go on to write. Then Trump appeared on the scene, and I found I could not stand to listen to him at all—not because I considered Putin better and Trump worse, per se, but because as I listened to Trump speak in my own language, my response was more primordial. The words got under my skin in a more visceral way. I felt physically nauseous—and implicated as an American. My Russian is obviously not nearly as deep and fluent as my English, but sometimes just for that reason I notice things in Russian, or in another foreign language, which I might not notice in my own.

***

I want to add just a few words about attachment and the Holy Grail of “objectivity.” Among the lessons I have taken from my three decades now as a student of history is not only the conventional postmodern understanding that there is no such thing as pure objectivity, but also the truth that attachment cannot be reduced to race, ethnicity, nationality, or any other obvious connection. In order to write we need to reach a level of intimacy with our historical protagonists. We develop attachments. When I began working on my book Caviar and Ashes, I was researching historical figures who were utter strangers to me. But by the end, they were no longer strangers. I felt more drawn to the poetry of some than of others. I respected some of their decisions more than others. Sitting in the archives, reading myself into their lives, I would sometimes feel admiring towards someone, or stunned, or sympathetic, at other times disappointed or disgusted. By the time I was ready to write—precisely because I was ready to write—I could no longer say that I was neutral, detached, “objective.” Notwithstanding the fact that my protagonists were dead, I had feelings about all of them.

This kind of developed intimacy overlaps with the intimacy that a translator develops with the voice of an author. Translation—like writing history—is an act of cultural mediation, explaining the lives of others to yet another audience, grappling with the border of what can and cannot be translated. No one can see inside another’s soul. And Freud taught us that we cannot even see completely into our own soul: our own selves are concealed from ourselves. There is no such thing as perfect clarity. Absolute Knowing—like the End of History—was always, and remains, a Hegelian illusion. At best we can adopt the Husserlian solution: describe the sides of the cube we can see vividly, with as much detail as possible. For the remaining sides, those not visible to us, we turn to others.

Marci Shore is Associate Professor at Yale University.

Diskuse