The Czech official narrative about the communist past is retrograde and politicized

29. 11. 2023 / Muriel Blaive

A critical view from German and Czech museums

All photos Muriel Blaive, 2023

Many thanks to Gérard-Daniel Cohen for his critical remarks on this text.

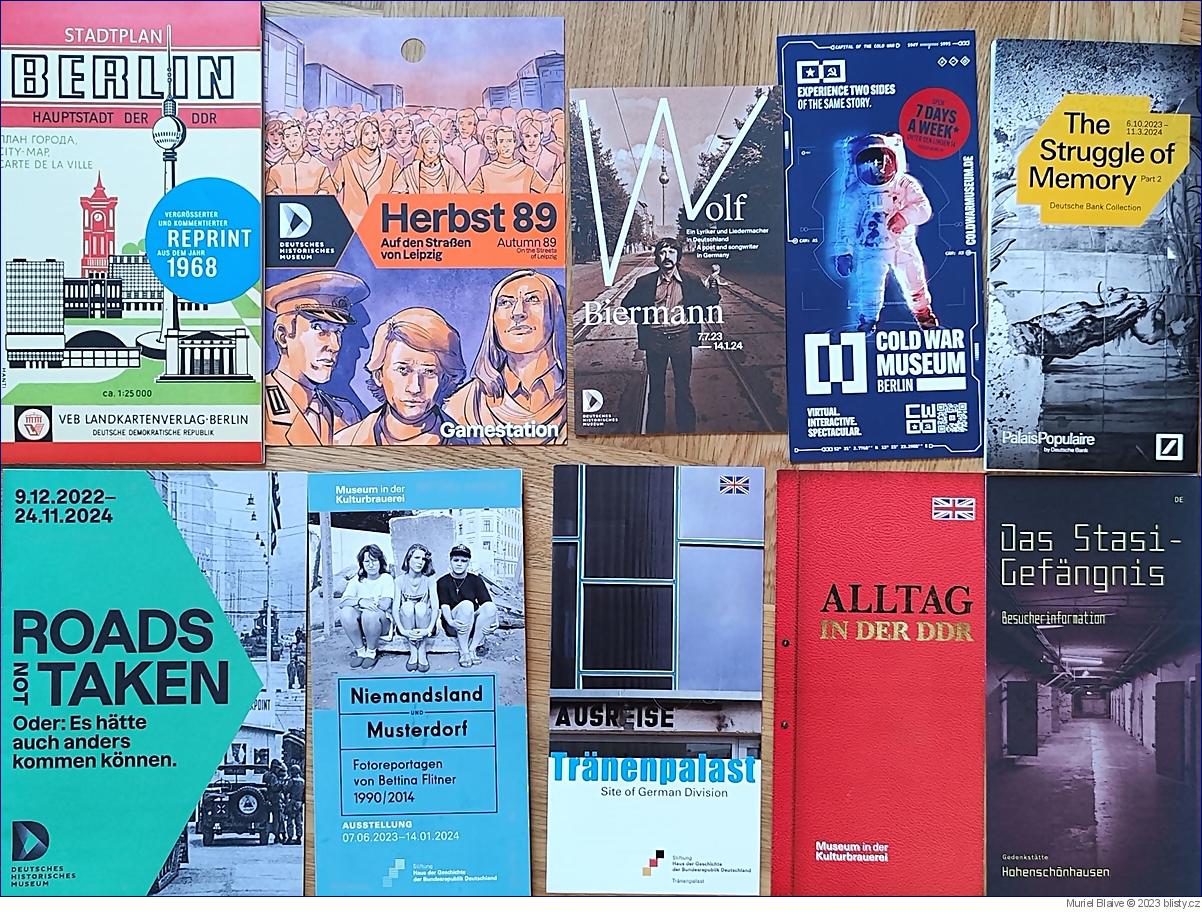

I recently visited eight museums dealing with the communist period in Germany: the permanent exhibition Everyday Life in the German Democratic Republic at the Museum in der Kulturbrauerei in Berlin; the temporary exhibits No Man’s Land and Model Village, by photographer Bettina Flitner, also at the Museum in der Kulturbrauerei; the Tränenpalast – Site of German Division in Berlin; the Cold War Museum in Berlin; the DDR Museum in Berlin; the temporary exhibitions Wolf Biermann – A Poet and Songwriter in Germany and Roads Not Taken. Or: Things Could Have Turned Out Differently at the Deutsches Historisches Museum in Berlin; the Berlin Wall Memorial in Berlin; and the Deutsch-Deutsches Museum Mödlareuth – Memorial to the Division of Germany in Mödlareuth at the border between Bavaria and Thuringia (ex-GDR), to which I would add the Memorium of the Nuremberg Trials in Nuremberg, which is of course concerned with the Nazi era but is an interesting methodological example, as well as various exhibits and memorials of the 1944 Allied landing in French Normandy which I previously discussed here. In Prague I also visited this year the permanent collection of the National Museum dedicated to the communist period, as well as the temporary exhibit Zneužitá muzea (Abused Museums.) I have also done previous work on the privately-owned Museum of Communism.

As I am generally interested in the methodology of representing the (communist) past to the Czech public, these German collections help me establish a comparative perspective. Of course, the main point of comparison in the Czech Republic is not one museum in particular, but rather the absence of a state-sponsored museum specifically dedicated to the communist era. I will come back to this point later as I argue that this absence is no accident. Meanwhile, I take as representative examples of Czech memory politics its various laws and regulations on the communist past (1990, 1991, 1993, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2011) or semi-public practices such as the leaking of the list of secret police collaborators by Petr Cibulka (1992), as well as the representation of the communist past in numerous popular media outlets (Lidové noviny, Respekt, Reflex, Forum 24, etc.), and in the public positions taken by the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes (ÚSTR) since the election of a new director in 2022.

The readers of Britské listy will be already familiar with my multiple appeals to make the history of communism in this country open up more widely to new methodological approaches, especially to a bottom up and everyday life angle, as well as to apprehend the communist period as a social negotiation between rulers and ruled. I have been called Marxist, neo-Marxist, communist, or even “typical French salon communist” for my efforts, and been variously accused of denying or trivializing communist repression in Czechoslovakia. The director of ÚSTR, Ladislav Kudrna, even hinted that what he calls my “revisionist” approach amounts to supporting Vladimir Putin and his war in Ukraine. Needless to say, these accusations are utter nonsense. I am no more a communist sympathizer than a supporter of Vladimir Putin. As far as I am concerned, Putin’s place is in the dock at the International Criminal Tribunal in The Hague for his crime against peace, war crimes, crimes against humanity and according to Timothy Snyder possibly even genocide committed in Ukraine.

But since the level of the Czech public debate on communist history in conservative circles is at times really that mediocre, it is not useless to look at the way the Germans deal with the musealization of their own communist past. I indeed derive my methodology of Czech communism from what I learned in the 2000s at the Zentrum für Zeithistorische Forschung in Potsdam, a methodology which is now dominant in Germany. Can the German approach to the study and representation of communism inspire Czech memory politics?

German museums attract all generations

The first striking element in the German museums I visited is that they are all very successful and are packed full with visitors. It certainly helps that the permanent and temporary exhibits at the Museum in der Kulturbrauerei, at the Tränenpalast, and at the Berlin Wall Memorial, including of course the latter’s outdoor exhibit, are free. The Deutsches Historisches Museum is free, too, but the temporary exhibits on Roads Not Taken and Wolf Biermann cost 10 euros together. The Cold War Museum and the DDR Museum are privately-owned and charge 16 and 13,50 euros respectively but are no less full for this. The German-German border memorial in Mödlareuth charges a modest 4 euros per entrance and the Memorial of the Nuremberg Trials costs 7,50 euros.

Considering the standard of living in Germany compared to the Czech Republic, German museums are cheaper and the patronage of the federal state and of the Länder is massive. Considering the amount of money Czechia has spent on enforcing its official narrative on communism in the past 15-20 years as a would-be “totalitarian period” of history, we might really wonder why the Czech state has not found the means to subsidize a free official museum of communism. Was it a lack of political will? I argue that it is and will explain why further down.

A second element I found moving in these German museums is that among the visitors we find many members of the grandparents’ generation, who evidently come to be reminded of their youth in the GDR. And they don’t just cry: they heartily laugh. I heard people describe to “Wessi” friends the vagaries of everyday life with a Trabant, gaily show various elements of socialist housing design to their grandchildren, giggle while pointing to everyday life objects and opening the cupboards and drawers of model socialist flats, and elbow each other with amusement while watching excerpts of socialist television programs.

But we also find in these museums many young people, including many groups of high school children and students. At every one of my visits there were several such groups. The way all generations are thus appropriating this history for themselves is not only deeply satisfying from the point of view of a public historian but is greatly contributing to social cohesion, to the mutual acceptance between the former east and the former west and ultimately, to the strengthening of German democracy. And indeed, compared to when I spent several months in Berlin in the 2000s, when one could retrace the location of the former wall just by walking on the street, the former east and the former west of the town are now nearly indistinguishable.

Deutsches Historisches Museum (top left), DDR Museum (top right, bottom left and right)

And a third element that goes hand in hand with the previous two is the quality and number of guided tours in the museums. Wherever I eavesdropped, the guides were remarkable: competent, visibly educated, and trained to be guides (no random citizen improvizing a narrative to make a few extra coins.) They gave not only facts and context but guided their visitors on how to reflect on history. And it was not rare to see two, three, or four tours taking place simultaneously in one and the same room.

Tränenpalast:

https://blisty.cz/video/Blaive.mp4

The concept of “everyday life” and the appropriation of history by ordinary citizens

Let us now examine the contents of the exhibits. Surely even Czech anticommunists acknowledge that East German citizens were submitted to communist repression. The Berlin Wall stood as a symbol of the whole “evilness” of communism, if such word can be used, and the Stasi was (in)famous for its suffocating surveillance of East German society. Yet German museums of Nazism and communism distinguish themselves by one presence and one absence compared to Czech memory politics: the unabashed presence of the concept of “everyday life” (the Museum in der Kulturbrauerei is even subtitled “Everyday life in the GDR”), and the complete absence of the concept of “totalitarianism.”

In the DDR Museum (but similar exhibits can be found in the other Berlin museums I mentioned), I visited a reconstructed socialist flat and learned about a Trabant boasting a foldable tent on its roof for a socialist-style vacation. I also read about leisure in the GDR, including about a possibly more satisfying sex life for women under socialism than in the West (a theory derived from the work of American historian Kristen Ghodsee.)

DDR Museum

Museum in der Kulturbrauerei

Where in Czechia the concept of everyday life history has been imbued, at least on the superficial level of the public debate led in the media and on social media, with the conviction that to be interested in the way people experienced the communist dictatorship on a daily basis amounts to denying the extent of communist repression, in Berlin the concept is at the basis of most, perhaps all, museal exhibits.

When Czech museums do use the concept of everyday life while referring to the communist period, for instance in the permanent collection at Národní muzeum and its temporary exhibit on “Abused museums” with the accompanying volume on “13 objects from an (un)happy museum”, a public scandal is artificially manufactured around it with the help of complacent media. The new leadership of the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes even weirdly attempted to stop the sale of the book issued from the 13 objects-exhibit even though it was produced by its own educational department. In this loaded context, the head of this department, Čeněk Pýcha, was fired, and the whole department collectively resigned in protest. Even before this episode, a digital schoolbook designed by the same department and operating with the same concept of everyday life and emphasizing the agency of social actors was publicly disavowed by the new leadership of the Institute and branded in the same complacent media as “post-factual” and “manipulative.” The message is clear: Czech authorities in historical matters are not about to let the country embark anytime soon on a vision of history leaving space to everyday life and examining the agency of social actors.

Let us note however that the permanent collection of Národní muzeum dedicated to the communist period, precisely because it leaves a large space to everyday life and to the famous “social negotiation” between the population and the regime (see image), is almost as successful as the ones in Berlin. I could observe there the same laughing and running children, although a difference is that I could see almost no contemporary witnesses of the communist period (who are now necessarily above 50 years of age.)

The (private) Museum of Communism in Prague is equally popular, although very few Czechs visit it – it has the stigma of being “made by an American who never experienced communism first-hand” (even though it is well curated and its collections are comparable to the Berlin museums mentioned above), and it is expensive for Prague: Kč 380 entrance fee (approx. €16) as opposed to Kč 280 (€11) for the Národní museum (which is prohibitive enough as it is.)

Altogether then, there is little doubt that a state-sponsored museum of communism would have no difficulty finding its public in Prague, especially if it were free. The public success of the “Rewrite history” (Přepište dějiny) podcast by Michal Stehlík and Martin Groman (Michal Stehlík is also deputy director of the Národní museum mentioned above), as well as the teaching material put together by the educational department of the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes before it resigned, including in English with the excellent program Socialism realised, show that there is no fatality in promoting a dogmatic anticommunist narrative in the Czech Republic. The material put together by the ÚSTR educational department (before it resigned) introduced in fact a complexity in teaching material that would work well in the Berlin museums. We might take as a representative sample the short film Back to the past, which shows socially disadvantaged agricultural workers fondly remembering the collectivization of agriculture implemented by the communist regime as it pulled them out of poverty – a narrative which is quite counter-intuitive compared to the usual image of victimhood associated to the collectivization of agriculture. This is a reflective and smart way to teach history.

The German way to render repression is subtle, yet efficient

Does the thematization of

everyday life mean that German museums deny the repressive dimension

of the communist regime? Not at all. Only Czech anticommunists

entertain the outlandish thought that everyday life is a negation of

repression.

DDR Museum

The Berlin Wall Memorial writes in its section “Dictatorship of Borders”: “The border system installed at the Berlin Wall revealed the true nature of the SED dictatorship. Everyday life in the GDR, however, was dictated by many other visible and invisible borders. The people were forced to subordinate themselves to the dictatorship. The SED dominated almost every aspect of society. It rewarded loyal conduct and punished those who crossed established boundaries. The closed borders only reinforced the strong pressures to conform that already existed. Nevertheless, by 1989, approximately 40,000 people had managed to escape the dictatorship by fleeing. Tens of thousands of people who wanted to flee were arrested and sentenced to prison. Others suffered fatal accidents at the border or were shot by border soldiers. In Berlin alone, at least a hundred people died during escape attempts. Another 38 people who were not trying to flee also died at the Wall.”

As the Czech reader can see, it is possible to include the words “dictatorship” and “everyday life” in the same sentence. In fact, it is not only possible, but it greatly enhances our understanding of the communist past.

Everyday life history is a unique vantage point from which to document repression

The Berlin Wall Memorial frames this methodological standpoint best in its juxtaposition of repression and everyday life themes in one common panel. When the theme of “shooting at the borders” is invoked, it features the oral history interviews of soldiers who did not want to shoot at potential escapees, yet were compelled to take their posts and did not dare to oppose the regime. In effect, the would-be evil arm of dictatorship is shown to have been constituted of concrete individuals who were enforcing a dictatorship without wishing it upon anyone. The people thus became their own repressor, their own surveillance police – just as I have abundantly showed in the case of České Velenice. This is why everyday life history is priceless: not because it denies repression but because it is a unique vantage point from which to document it.

Berlin Wall Memorial

Also in Mödlareuth, dubbed

“Little Berlin” because here, too there was a portion of wall

between Thuringia (former GDR) and Bavaria (FRG), the explanatory

film which can be watched in the museum is entitled “Everyday life

at the border.”

Deutch-Deutsches Museum Mödlareuth

Totalitarismus raus!

Whereas the “everyday” is present everywhere in German museums in reference to the communist past, as opposed to the Czech anticommunists’ discourse on the would-be totalitarian character of the communist rule the word “totalitarian” does not appear anywhere: only the word “dictatorship” is used.

“Totalitarianism” has become in Czechia since 1989 a catchword to transform the negative qualities of the communist rule into an ideological, abstract “evil.” The people who support the “totalitarian narrative” have surrendered to the facile temptation to instrumentalize their narrative of the past for political purposes primarily in order to discredit the left in post-communist times. This narrative might have sounded appealing on a superficial level for the people which were understandably angry at communist leaders after 41 years of dictatorship. However, it is problematic insofar as what is abstract does not translate into concrete individual responsibilities. Any individual story will illustrate the fact that life was not black and white under the communist dictatorship and that everyone had to make small concessions here and there. Hence, there is no such thing as totalitarianism: what we have is human beings flawed at various degrees who tried to do their best to survive in difficult circumstances and who might have been anonymous small-scale heroes or anonymous small-scale perpetrators – and more often than not, a bit of both.

The totalitarian narrative is so structurally flawed it can be sustained only if it remains very vague. As paradoxical as it may seem, the proponents of “totalitarianism” are therefore, in fact, the people who are the least likely to identify, judge, and sentence actual communist criminals. Indeed, justice does the opposite of ideology: it focuses on concrete cases. And as the totalitarian mindset took hold of the Czech public discourse on the communist past already in the course of the 1990s, this is one of the reasons why so few Czech communist criminals have been brought to court and sentenced for their crimes committed against socialist legality, let alone against international human rights. Everyday life history would have been the best and perhaps the only useful background to help expose communist crimes and to actually punish them. To acknowledge that the Czech nation entertained a complex relationship with the communist rule, suffering from repression on the one hand, but supporting other aspects of the regime and being indifferent to yet others, is not a way to belittle this repression but to dissect it and account for it.

No martyrology competition in Germany

This is the reason why German memory politics are keen to reflect on everyday life side by side with repression. As opposed to the Czech case, as least as seen from the narrow anticommunist angle which dominates in Prague (albeit not necessarily in the rest of the country), the terms of dealing with the communist past could not be, and were not, instrumentalized for political purposes in Germany.

Reunified Germany was indeed in a peculiar and fragile position as the successor state of both Nazism and communism. Had it instrumentalized the communist past to undermine the left as the Czech public sphere did, it would have pitched one part of the country against the other and would have provided ammunition to potential supporters of the Nazi era. Its only rational choice was to try and understand what the people went through, under both Nazism and communism, as well as to endeavor after 1989 to judge and sentence the people responsible for the communist repression.

This attitude was, by the way, largely influenced by the country’s four decades of reckoning with the Nazi rule, itself initiated by the Western occupants – let us remind that the Nuremberg trials were held at the initiative of the Allies, and without belittling the part taken by the Soviets at the trials, it is by Western powers that the Federal Republic was occupied and geared towards dealing with its own past. Czechoslovakia of course did not benefit from this opportunity. But even the GDR was more advanced than other communist countries on its reckoning with the Nazi rule, certainly due to its rivalry with the Federal Republic as to who was the “better” Germany. In any case, the Federal Republic had the unparalleled privilege to have at its disposal in 1989 an army of historians who had been trying for years to account for the support of the German population to Nazism and who had already developed a whole methodology of bottom up and everyday life history, as well as of practices of domination and agency of social actors (Herrschaft and Eigen-Sinn.) All they had to do after 1989 was to transfer and adapt their methodology to the new research terrain of (post-)communist society.

This is how West German historian Bernd Faulenbach, who presided in 1991 an expert committee to develop a new concept for the Sachsenhausen memorial, introduced a formula that was to become the “golden rule for further decision-making, acts of legitimization and truth production in this extremely sensitive field” (Thomas Lindenberger.) The “task of meting out justice to both groups of victims of tyranny” was defined by a double limitation within German memory politics:

“Neither must the Nazi crimes be relativized by the crimes of Stalinism, nor the crimes of Stalinism be trivialized by hinting at the Nazi crimes.”

This does not amount to saying that there is the same number of victims under either dictatorship, or that the latter are equally “evil” as the proponents of totalitarianism would have us believe, but simply that all victims deserve empathy. Because there could be no martyrology competition between the victims of Nazism and those of Stalinism without causing considerable damage to the fragile, reunified German social fabric, German memory politics have been geared ever since 1990 towards establishing individual responsibilities and reconciliation rather than towards issuing blanket condemnations and collective accusations and rehabilitations, as has been the characteristic in Czech official memory politics since the Velvet Revolution.

Conclusion: Czech official memory politics are fundamentally flawed

This explain why the Czech state has been incapable to date of sustaining a historical narrative of communism that could speak to a large part of the population: it enforces, against many of its own museal experts, both a heroization narrative that very few people can relate to and a martyrology narrative that denies the genuine positive aspects of the communist rule that many people still have not forgotten. The result is an ideological narrative of anticommunism which too few people can appropriate to make it publicly sustainable on the national level, at least for the time being. This is the reason why there has not been, and cannot be, any state museum of communism yet. The public cannot appropriate and endorse a narrative if they don’t relate to it. The project of a new, oddly named Museum of twentieth century memory, which promises to be yet another anticommunist outlet, is stumbling at present but even if it succeeds, it is already obvious that it will not speak to a wide segment of the population either.

This Czech official memorialization also means that as opposed to the German way, which was geared towards reconciliation ever since the first sentences of communist criminals were pronounced, the Czech state narrative cannot possibly lead to any form of reconciliation. It maintains Czech society in an everlasting limbo of neither forgetting communism nor being able to settle accounts with the communist rule. Its only result has been to divide society to the profit of populists and of the right. This has almost nothing to do with history, and everything to do with political instrumentalization.

Diskuse